On June 28, 1919, the Texas legislature approved a resolution ratifying the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote. Texas was the ninth state in the U.S. and the first state in the South to ratify the amendment. By August of 1920, 36 states (including Texas) had approved the amendment and it became part of the United States Constitution.

A History of the suffrage movement in Dallas

To see the entire lecture, Suffrage in Dallas, CLICK HERE

Texas Suffrage Milestones

The Road to Ratification

In late 1918, Texas suffragists opted to postpone proposals for a state constitutional amendment until after World War I. They chose instead to work for ratification of the federal amendment. This was in keeping with the National American Suffrage Association's philosophy, as the passage of the federal amendment was expected in January of 1919.

The Texas Equal Suffrage Association formed a Ratification Committee, chaired by Jane Y. McCallum, in anticipation of the efforts necessary to lobby the Texas Legislature for ratification once the federal amendment was passed. Minnie Fisher Cunningham moved to Washington, D.C. to lobby southern Democratic Senators about ratification on a national scale.

Although the U.S. Senate failed to pass the federal amendment in January, Texas Governor William P. Hobby signed the full suffrage bill on February 5, 1919. Suffragists launched an intensive campaign but the May 24 election, mandated by the suffrage bill, ultimately resulted in the amendment's defeat. Election fraud and irregular election ballots were a major cause.

On June 4, 1919, the U.S. Senate passed the federal suffrage amendment. By June 28th, the Texas Legislature had ratified the amendment, making Texas the ninth state in the Nation, and the first in the South, to do so.

Primary Suffrage in Texas

In Texas, the struggle for woman suffrage was carried out amidst the political turmoil of the Ferguson era. Governor James E. Ferguson, whom suffragists viewed as the "implacable foe of woman suffrage and of every great moral issue for which women stood," was inaugurated on January 12, 1915. After a bitter controversy involving Ferguson's efforts to control the University of Texas' faculty, finances, and Board of Regents, the Texas Senate voted to impeach Ferguson in September of 1917.

At its January 1918 board meeting the Texas Equal Suffrage Association took action. William P. Hobby, who had assumed the governorship upon Ferguson's departure, was asked to submit the primary suffrage bill at a special legislative session scheduled to convene February 26th to consider prohibition. In return, the group promised to "use its influence and organization to assist him in his campaign for Governor."

The primary suffrage bill, introduced by San Angelo representative Charles B. Metcalfe, passed both the House and Senate and was signed into law by Hobby on March 26, 1918. The law went into effect only seventeen days before the July 27th primary and a highly publicized registration drive that opened on June 26th. In Travis County, 5,856 women were registered -- a number almost equal to the expected number of male voters.

African American Women and the Vote

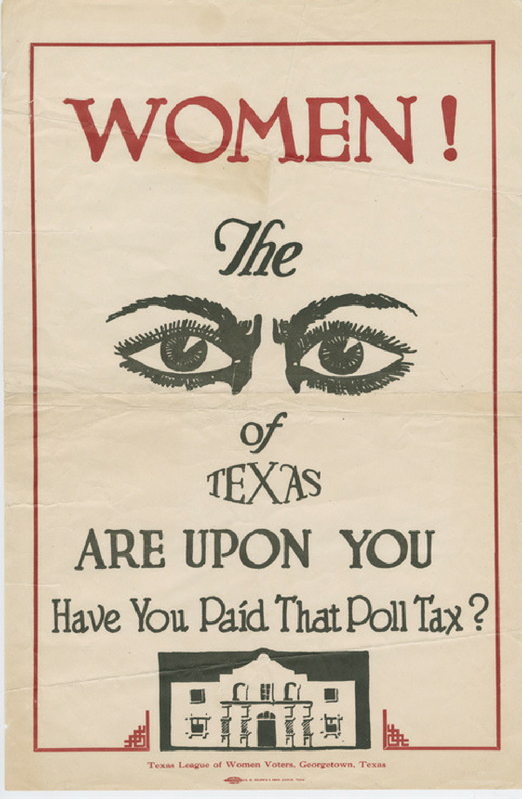

African-American women had been excluded from the suffrage movement. Many black leaders had opposed suffrage, in part because of the belief that a woman's place is in the home, and in part because they feared reprisals against African Americans if black women exercised their right to vote. Most African-American Texans were disenfranchised by laws such as the poll tax, literacy tests, and the white primary, which restricted voting in the Democratic primary to whites only. The passage of the 19th Amendment made no real difference in their political status.

African-American women had been excluded from the suffrage movement. Many black leaders had opposed suffrage, in part because of the belief that a woman's place is in the home, and in part because they feared reprisals against African Americans if black women exercised their right to vote. Most African-American Texans were disenfranchised by laws such as the poll tax, literacy tests, and the white primary, which restricted voting in the Democratic primary to whites only. The passage of the 19th Amendment made no real difference in their political status.

However, African-American women were not strangers to community activism. Often through church groups or organizations like the Urban League and the NAACP, African-American women put their energies into trying to alleviate problems in their communities caused by poor conditions for working women, limited economic opportunities, inferior housing, and discrimination. Their passions were education and health care for children and the elderly.

Tejano Women and the Vote

Tejanos had been largely excluded from Texas politics from statehood on. Like African Americans, Tejanos in the early 20th century faced discrimination in employment and education and violence against them if they stepped out of line. To combat these problems, they formed mutual-aid societies on the local level. Laredo women had blazed the trail for the formation of women's clubs to help serve the poor and work for improved education and health care for their people. The 1920s saw an expansion of the women's club movement for Hispanic women. For example, the Cruz Azul Mexicana club in San Antonio raised money for a free medical clinic, established a library, and offered legal assistance to workers and immigrants. Hispanic women also became involved in the PTA during the 1920s.

Fair Park's Connection to the Suffrage Movement

Fair Park was established in 1886. It was the location of the Texas State Fair. In 1893, the fair featured a woman's congress of over 300 women. The congress was organized by suffragist Dr. Ellen Lawson Dabbs, secretary of the Texas Equal Rights Association. From 1913-1917, the fair also featured a “Suffrage Day” when local suffragists would gather and promote women’s voting rights.

Pivotal Figures in Texas Suffrage

Minnie Fischer Cunningham

Born in New Waverly, Texas, Minnie Fisher Cunningham was the first executive secretary of the League of Women Voters and a suffrage politician who worked for the passage of the nineteenth amendment to the United States Constitution, giving women the vote.

Born in New Waverly, Texas, Minnie Fisher Cunningham was the first executive secretary of the League of Women Voters and a suffrage politician who worked for the passage of the nineteenth amendment to the United States Constitution, giving women the vote.

A political worker with liberal views, she became one of the founding members of the Woman’s National Democratic Club. In her position overseeing the club’s finances, she helped the organization purchase its Washington, D.C. headquarters, which is still in use today.

Christia V. Daniels Adair

Christia was born in Victoria, Texas. She came to Austin to attend Samuel Huston (now Huston-Tillotson) College, then continued her education at Prairie View A&M. She married Elbert Adair in 1918. Adair became a teacher in Kingsville and joined a biracial group opposed to gambling. She also became one of the few African-American suffragists in the state.

Christia was born in Victoria, Texas. She came to Austin to attend Samuel Huston (now Huston-Tillotson) College, then continued her education at Prairie View A&M. She married Elbert Adair in 1918. Adair became a teacher in Kingsville and joined a biracial group opposed to gambling. She also became one of the few African-American suffragists in the state.

Disillusioned when she was still denied the vote after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, Adair became an early member of the Houston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. During her tenure as executive secretary of the Houston branch from 1943-1959, she helped in the landmark Smith v. Allwright case, which ended the Texas “white primary.” Adair also helped desegregate the Houston Public Library, airport, veterans hospital, city buses, and department stores. She also helped win the right for blacks to serve on juries, be hired for county jobs, and to be addressed in the newspapers with the same titles of respect used for whites.

Jessie Harriet Daniel Ames

Jessie Daniel Ames, suffragist and anti-lynching reformer was born in Palestine, Texas. In 1893 the family moved to Georgetown where Jessie entered the Ladies Annex of Southwestern University at the age of thirteen. She graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1902. After the deaths of her father in 1911 and her Husband Roger in 1914, Jessie helped her mother run their Georgetown Telephone Company for a brief time before she organized and presided over the Georgetown Equal Suffrage League in 1916.

Jessie also began to write a weekly “Woman Suffrage Notes” column for the Williamson County Sun. In 1918, Jessie was elected Treasurer of the Texas Equal Suffrage Association; From this position she helped to make Texas the first southern state to ratify the nineteenth amendment.

In 1985 the Jessie Daniel Ames Lecture Series was inaugurated at Southwestern University, and Jessie Ames’s life and work were the subject of both the university’s 1985 Freshman Symposium and its 1986 Brown Symposium.

Offices and Appointments Held

- Texas State League of Women Voters; Founder & President

- National League of Women Voters at the Pan-American Congress; Representative

- National Democratic Convention; Delegate-at-large,

- Texas branch of the American Association of University Women; President

- Women’s Joint Legislative Council; Officer

- Board of Education (Women’s Division); Officer

- Texas Committee on Prisons and Prison Labor; Officer

- Texas Federation of Women’s Clubs; Officer

- Texas Council of the Commission on Interracial Cooperation; Director

- National Council of the Commission on Interracial Cooperation; Director

- Association of Southern Women; Director

Related Articles

Women Who Made a Difference

Legacies: A History Journal for Dallas and North Central Texas, Volume 13, Number 2, Fall, 2001

CLICK HERE to read this article

Not Organizing for the Fun of It

Suffrage, War, and Dallas Women in 1918

By Melissa Prycer, Dallas Heritage Village

CLICK HERE to read this article